The “Crazed Fan” Problem: Why Stopping at the Spectacle Lets the Real Dangers in Fandom Thrive

If “crazy” is the disease, what’s the remedy?

Last week, a woman harassed Keanu Reeves outside the Broadway theater where he’s currently performing, chasing after his car as he was trying to go home. Within hours, headlines and TikToks reduced the moment to a familiar phrase: “crazed fan.”

It’s an easy label…neat, dramatic, and very clickworthy. But stories like this are rarely that simple.

I can’t possibly assume this woman’s motives or intentions, and I wouldn’t want to. What I can do is hope that everything possible is being done to protect Reeves as he continues performing each night. But because this happened to an actor whose team has reportedly filed more than 40,000 takedown requests for impersonation accounts over the past year, I couldn’t help thinking about how quickly we stop at the spectacle instead of asking what fuels it.

Back in July, The Hollywood Reporter published a deep dive into the world of celebrity impersonators, and it is a fascinating read. The sprawling industry uses fake accounts, doctored videos, and even AI-generated voices to scam fans, often targeting older individuals. According to the report, Keanu Reeves is among the most impersonated celebrities online, with his team paying a company thousands of dollars a month to initiate takedown requests.

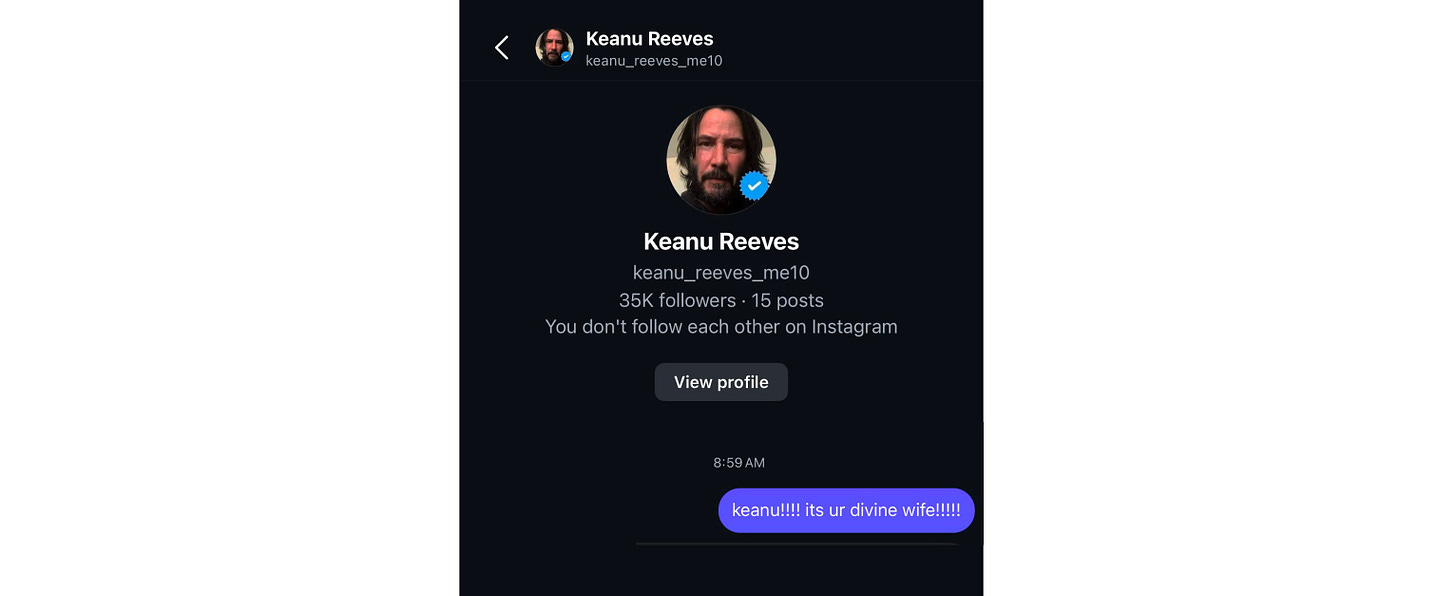

Scammers frequently use messaging apps like Telegram or WhatsApp to pose as him, asking victims for money, fan club fees, or even emotional support. In some cases, victims are led to believe they’re in a romantic relationship with Reeves himself. The woman who recently followed Reeves to his car outside his Broadway show notably can be seen referring to herself as his “divine wife,” a belief consistent with the kinds of manipulative, delusional relationships that impersonators cultivate.

As artificial intelligence technology continues to evolve, these deceptions are becoming more convincing, and as a result, incredibly more dangerous.

Dogstar, Reeves’ band, has even pinned a warning to the top of their Instagram page, writing “There are no ‘private accounts’ or ‘secret pages,” and “Keanu does not have any social media.”

Still, that context disappears the moment a story gets published. It’s easier to slap “crazed fan” into a headline than to confront the complex ecosystem that made such behavior possible in the first place. But we simply cannot solve any problems if we stop at name-calling.

Why is she a “crazed fan”? What happened to her that didn’t happen to every other person at the stage door? These incidents are outliers, yet we never treat them that way. We’d rather burn down the entire infrastructure of fandom as a knee-jerk reaction to one bad actor in a crowd of many. And I get it…if that happened to me outside a theater, I’d be TERRIFIED. One person’s outburst can cause irreversible harm. But stopping there would only protect myself. The underlying problem would still persist, and the “crazed fan” still needs help.

This pattern isn’t limited to Broadway. It’s happening across the entertainment industry. Artists once engaged directly with fans, whether it be through Twitter replies, livestreams, and meet-and-greets. That was until the environment was deemed too toxic and invasive. Many artists stepped back, letting their labels and PR teams manage “artist HQ” accounts and other fan engagement outlets that replicate closeness without the artist ever logging on.

On the surface, this seems safer. The artist is protected from the “crazed stans” online. But the fan experience hasn’t actually changed. It’s simply becoming more commercialized. The same marketing strategies that once built genuine connection are now used to simulate it.

The result is a cycle that quietly endangers everyone. The industry keeps fueling closeness to sell records and tickets without any infrastructure or protections for when the parasocial attachments go too far.

When the stigma says fans are supposed to be crazy anyway, it becomes easier to call them that and move on. If the stereotype already exists, you don’t have to think, you simply have to point. But when we do, we focus on inevitability and not preventability, and we stop identifying the very factors that could prevent escalation.

What I wish is to see less sensationalism and more solutions. If we keep mocking or villainizing fans instead of educating them, we create the perfect conditions for more impersonation scams, emotional manipulation, and dangerous misunderstandings. Protecting fans isn’t the opposite of protecting artists. It’s all part of the same goal.

With the Keanu Reeves situation, conversation in fan spaces quickly turned into a debate about stagedooring and whether fans should even be allowed to wait for performers after shows. To be completely honest, I think we are at a point where that is a very valid conversation. Stories like this are becoming increasingly common within the Broadway community and safety should always be taken seriously first. But taking away the barricade may not be the sole action to fix the behavior.

If someone is being scammed, manipulated, or struggling, they’ll just find another outlet. The question shouldn’t stop at whether fans should stand outside a stage door, but examine what’s pushing people to that edge in the first place and how we can prevent it from happening again.

We can’t fix what we refuse to understand. So what can we actually do?

For fans:

Stay skeptical. If a “celebrity” DMs you asking to move the chat to Telegram or WhatsApp, it’s a scam. Don’t pay for “fan club cards” or “private calls.” If something feels off, report it and warn others, without shame.

For artists and teams:

Be proactive. Follow Dogstar’s lead. Pin a clear post listing verified accounts and stating that you’ll never DM fans for money or personal info. A quick PSA could save susceptible people from real harm.

For media and platforms:

Change the narrative. Sensationalized headlines get clicks, but context about scams, exploitation and internet safety can actually help people. Adding a single line acknowledging the rise of impersonation scams or manipulation trends can help other fans learn online risks and hold platforms accountable for removing fake accounts quickly.

It’s easy to laugh off these stories as fandom gone wild. It’s harder, but more honest, to admit that we’ve built a culture where intimacy is marketed, trust is monetized, and deception thrives in the gaps. Fandom isn’t going away, and neither is the internet. The solution isn’t to punish symptoms, but address causes.

If someone’s admiration and emotional investment is exploited and turns chaotic, everyone loses. Fans lose money and dignity, artists lose a sense of trust and security, and the general public loses another piece of faith in the positive community fandom can bring.

The woman outside that theater was a “crazed fan.” What she did was wrong. But reducing it to that phrase explains nothing. It only ensures we’ll see it happen again. If we want fandom to get healthier, we have to move past outrage and start asking why. When understanding disappears, exploitation has room to take its place, and things only get more unsafe for everyone involved.

Giving fans the tools they need to stay safe is one important step towards a better fandom environment.